All About the People and Land of Iran

By: Mohammad Hassan Talebian

Present-day Iran is part of a much larger geographical unit called the Iranian plateau. This natural unit, although climatically and biologically diverse, has a number of common characteristics that have led to, and perpetuated, a kind of "cultural unity". Iran presently is heir to a reality that is known as the "Iranian world". Human civilization has immensely benefited from the ingenuity and creativity of the people who lived in this land. Interacting with nature, they managed to gradually build and develop their civilization and culture and, by doing so, enduringly influenced history and human development which is apparently evident. Native rulers and the Iranian people never lost faith in the destiny of the Iranian nation; challenges and disasters only served to solidify national resolve. The nation never wavered and remained true to its lofty ideals. The evidence relating to the first cultural behaviors of man in Iran starting from manufacturing assorted stone tools that pertain to the Paleolithic period dates back to 200,000 years ago. There is ample evidence of human settlement in many parts of Iran. Communities thrived around Lake Urmia in the North West and in Shiraz in the South West, and also the southeastern shores of the Caspian Sea and further items such as Kashaf-Rood in Khorasan, Sistan, the Maraghe fields, the cave and shelters of Khoram-Abad valley, Homiyan in Koohdasht, Helilan valley in Lorestan, Maydasht caves in Bisotoon and Kermanshah have yielded evidence of the cultural life of Paleolithic Man. By the end of this period, Mesolithic Man -- aside from hunting and gathering -- was storing some of his food, thus setting the stage for extensive cultural and economic developments.

Later, huge steps were taken leading to the establishment of settlements and production. Evidence pertaining to the above-mentioned stage has been recovered from the grounds and caves of Khoram-Abad Valley, around the Kur River in Fars, and on the outskirts of the province of Behshahr. Moving away from the Paleolithic age, around 12000 BC the inhabitants of the Near East including those living on the Iranian Plateau, reached the Neolithic age of their cultures and civilizations. This stage of development is characterized by farming, the domestication of farm animals, and the final metamorphosis of townships. The production of clay, increased agricultural and animal husbandry expertise, and improved architectural techniques. Moreover, higher levels of industrial and vocational mastery are the other characteristics of this period. It must also be mentioned that cultural spheres in the Iranian Plateau gradually became distinguished from one another. The Sialk tepe, Cheshme Ali and Hesar in the central plains of Iran, Giantepe, TepeGoran, Sar-Abb, Gooden and Ganj Dareh in the West, and also Ali Kosh, Chogha-Mish, and Susa in the southeast, as well as Ba-Gavan in Fars, are the main bedrocks of western Asian culture and civilization in Iran.

|

The Neolithic age lasted well into 5000 BC. At the end of this period what is known as present-day Iran, along with the rest of its surrounding plateau in West Asia, entered a period in which metal was mass-produced, a transition was made from small towns to cities, and writing, measures, and signs were invented, helping to develop trade, architecture, industry, recording of past events, literature and the arts. During this period, Iran, with its geographical, climatic, and cultural diversity, managed to greatly influence all aspects of culture and civilizations around it in an integrated manner. The emergence of the powerful and enduring Elamite rule in a substantial portion of the southwest with the 5000-year-old city of Susa as its inimitable gift to the age, alongside other Iranian cities such as the Shahr-e Soukhte (burnt city) in Sistan, the extended fields of Halil-Rood in Jiroft and the specialized smelting and metal recovery township in Arisman, all point to the role played by the Persian civilization and its contribution to the development of science and industry. The people's deep devotion to spirituality, religion, art, and contemplation was manifested in the construction and creation of glorious, religious, and stately works and buildings, such as Ziggurat Chogha Zanbil, or artistic works of clay. The above period included the important Iron and Bronze Ages and lasted well into the first millennium BC. In the middle of the first millennium BC, with the arrival of the Aryan tribes, Iranian culture and civilization reached new heights of excellence, power, and creativity lasting more than 1000 years.

The Achaemenid dynasty, I .e.the rule which emerged from the land of Persia, extended to cover the old world entirely. It also managed to control the pulse of the region's culture and civilization for 200 years. The remnants of Takht-e Jamshid, Pasargadae, and Naghsh-e Rustam amply showcase the Iranian people's religious, God-seeking, intelligent and resourceful spirit. The Achaemenid's mastery of authority, political, social, and economic openness continues to inspire the world of politics and good governance. The architectural ingenuity, masterful engineering, and artistic prowess of Iranians in that period came together to greatly advance human civilization. Mention must also be made of their mastery over the region's a trade and transportation routes, influence over the governance and the leadership style of lands under their rule, the establishment of a financial and monetary system, and the circulation of coins. In the same period, magnificent works of art were created. Wood, stone, and ivory carvings as well as glass and metal objects of art and textiles came to rank amongst the most magnificent artistic and technical achievements of the old world. The grandeur and fame of the Persian rulers of the known civilized world were so awe-inspiring that, after Alexander attacked Persia, the new rulers presented themselves as Achaemenid kings and heir to the Achaemenian tradition. Despite short disruptions resulting from the Alexander of Macedonia's assault, another Persian government, this time from the northeast and known as the Parthians continued the development of eastern culture and civilization and ruled for more than 400 years. They competed with Rome to rule the then-known world of the time. Their nationalistic innovations, drive to expand and promote their culture and civilization, success in establishing new trade routes, organization of a successful commercial, monetary and financial system, script, writing, art, and a network of major cities including Balkh, Nesa, Ray, Hamadan, and Ctesiphon was instrumental in the establishment of a new global empire. Innovation in architectural design, the use of arches for gateways and residential spaces, the use of terraces overlooking courtyards, the introduction of arching terraces in place of the Achaemenid pillared terraces, and also the use of such materials as adobe, bricks, and a gypsum mortar produced and showcased a new golden age of Persian architecture, Extensive political, military, and economic contact between the Parthians alongside their extensive borders with the Romans on the one hand and their equally extensive ties with the Kushan dynasty, their other neighbor to the east, was a measure of their might and national organization. Other evidence, including the production of diverse earthenware with their increasing use of glazing - glass and stone objects, etc. all point to their ability to the mass-production of goods, as well as their access to lucrative markets, commercial vibrancy, and increasing public welfare and treasure. At the beginning of the third century AD, another dynasty rose from the land of Persia to revive the memory of the Achaemenid Empire: the vigorous, centralized, and nationally cohesive rule of Ardashir Babakan. In a short span of time, the new dynasty managed to overcome all regional opposition and to solidify its rule over the land of Persia. It ruled nearly 400 years and, like Parthians, the previous dynasty, worked to safeguard the Persian identity, vehemently competed with Rome in the west, and suppressed the invading hordes to the east.

In the third century AD, following a series of battles with the Persians, the Romans were defeated and three Roman emperors were either killed or captured. Shapur I immortalized these battlefield victories in extensive rock carvings in Naghsh-e Rustam and rock relief at Tang-Chogan, Naghsh e Rustam, and Darabgerd (all of which are in Fars). The establishment of numerous cities, architectural and engineering creativity, and the intelligent use of gypsum mortar in the construction of stately and grand buildings are striking characteristics of the period (as seen in Ghale-Dokhtar, Kakh-e Firoozubad, the cross-shaped building, and the temple of Anahita in Bishapur, Kakh-e Sarvestan, and Tagh-e Kasra). The use of circular plans for city building (as in the city or Firouz-Abad), the establishment of an academy in the city of Jundishapur (Khuzestan), the promotion of arts, vocations, and industrial specialization, the creation of trade routes and networks, an effective monetary system, and the regular minting of gold and silver coins were achievements that later aided the emergence and spread of Islam. These achievements continue to inspire and enrich Persian identity up to this date. The Sasanids prospered by constructing extensive hydro-installations, a network of roads, bridges, defense installations, religious temples, and glorious official buildings, and by developing their engineering and architectural skills. They also manufactured exquisite textile, metal (especially silver) and glass pieces, coins, seals, etc. which today adorn many highly regarded museums around the world. Persian coins, carried by caravans and exchanged throughout many trade routes, found their way to the four corners of the old world including China, Japan, Korea, the Far East, Central Europe, and Scandinavia. This is an indication of the global reach of the Sassanid dynasty. In the seventh century AD with the emergence of Islam and its adoption by the Persians led to its quick spread through the near East - especially in Persia and Central Asia.

The Iranians contributed their wealth and might in support of another divine messenger. Their steadfastness and perceptiveness resulted in the birth of a dynamic school, from the very heart of the Islamic society, called Shi'ism. Islamic thought and knowledge, in its Persian manifestation and bedrock, experienced many highs and lows through the centuries. The emancipation of Persian from the rule of the Caliphs, the growth and spread of the Persian language, and the establishment of nationalistic rules were reasons enough for Persian ingenuity and their restless soul to compel different Islamic cultural and civilizations Spheres to accommodate them. Although present Iranian borders are much smaller than they were in previous centuries, they are broad enough to accommodate a glorious chapter of Iran and Islam. Despite the Extensive political, military, and economic contact between the Parthians alongside their extensive borders with the Romans on the one hand and their equally extensive ties with the Kushan dynasty, their other neighbor to the east, was a measure of their might and national organization. Other evidence, including the production of diverse earthenware with their increasing use of glazing - glass and stone objects, etc. all point to their ability to the mass-production of goods, as well as their access to lucrative markets, commercial vibrancy, and increasing public welfare and treasure. At the beginning of the third century AD, another dynasty rose from the land of Persia to revive the memory of the Achaemenid Empire: the vigorous, centralized, and nationally cohesive rule of Ardashir Babakan. In a short span of time, the new dynasty managed to overcome all regional opposition and solidify its rule over the land of Persia. It ruled nearly 400 years and, like Parthians, the previous dynasty, worked to safeguard the Persian identity, vehemently competed with Rome in the west, and suppressed the invading hordes to the east. In the third century AD, following a series of battles with the Persians, the Romans were defeated and three Roman emperors were either killed or captured. Shapur I immortalized these battlefield victories in extensive rock carvings in Naghsh-e Rustam and rock relief at Tang-Chogan, Naghsh-e Rustam, and Darabgerd (all of which are in Fars).

The establishment of numerous cities, architectural and engineering creativity, and the intelligent use of gypsum mortar in the construction of stately and grand buildings are striking characteristics of the period (as seen in Ghale-Dokhtar, Kakh-c Firoozubad, the cross-shaped building, and the temple of Anahita in Bishapur, Kakh-e Sarvestan, and Tagh-e Kasra). The use of circular plans for city building (as in the city or Firouz-Abad), the establishment of an academy in the city of Jundishapur (Khuzestan), the promotion of arts, vocations, and industrial specialization, the creation of trade routes and networks, an effective monetary system, and the regular minting of gold and silver coins were achievements that later aided the emergence and spread of Islam. These achievements continue to inspire and enrich Persian identity up to this date. The Sasanids prospered by constructing extensive hydro-installations, a network of roads, bridges, defense installations, religious temples, and glorious official buildings, and by developing their engineering and architectural skills. They also manufactured exquisite textile, metal (especially silver) and glass pieces, coins, seals, etc. which today adorn many highly regarded museums around the world. Persian coins, carried by caravans and exchanged throughout many trade routes, found their way to the four corners of the old world including China, Japan, Korea, the Far East, Central Europe, and Scandinavia. This is an indication of the global reach of the Sassanid dynasty. In the seventh century AD with the emergence of Islam and its adoption by the Persians led to its quick spread through the near East - especially in Persia and Central Asia. The Iranians contributed their wealth and might in support of another divine messenger. Their steadfastness and perceptiveness resulted in the birth of a dynamic school, from the very heart of the Islamic society, called Shi'ism. The Islamic thought and knowledge, in its Persian manifestation and bedrock, experienced many highs and lows throughout the centuries. The emancipation of Persian from the rule of the Caliphs, the growth and spread of the Persian language, and the establishment of nationalistic rules were reasons enough for Persian ingenuity and their restless soul to compel different Islamic cultural and civilizations Spheres to accommodate them.

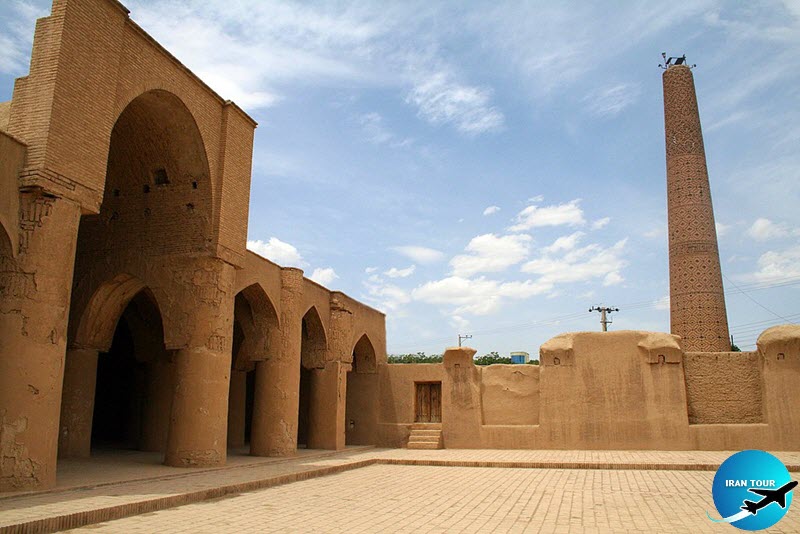

Although present Iranian borders are much smaller than they were in previous centuries, they are broad enough to accommodate a glorious chapter of Iran and Islam. Despite the many catastrophes and harms inflicted on it-such as the onslaughts by the Mongol hordes, Iran managed to remain at the very heart of artistic and cultural innovation in the Islamic world. The construction of terraced courtyards, as well as four terraced courtyards, arching roofs, enlarged domes and minarets, architectural decorations such as plaster ornamentation, tiles and painted designs, usage of decorative stones and lighting effects reflecting off smooth beds of multicolored tiles, and spiraling and twisting plasterwork were strokes of genius that continue to mesmerize onlookers even today The spiritual aura of Masjid-e Jame, Masjid-e Shah and Masjid-e Sheikh Lotfollah mosques in the city of Isfahan, or the tranquility and elegance of Iranian walled gardens including the Bagh-e Fin garden in the city of Kashan and Bagh-e Shahzad in the city of Mahan located in Kerman province are undeniable. To those are added the art of constructing qanats, bridge, and water capes such as Pol-e Khajoo and Sei o se Pol, and fort, ramparts, and defensive walls such as the one found in Ghale Hassan Sabbah(Sabbah fortress) in Alamut, Gerd-Koohin Semnan, Bam Citadel, and the defensive wall surrounding Gorgan. Mention must also be made of grand Iranian bazaars. Great bazaars, such as the Tabriz Bazaar and Gheisarieh Bazaar in Lar were an integral part of the social, political, economic, and cultural life of the day, and al 0 provided a safe location for the fabrication of different goods.

Iranians were also master wood crafters, they masterfully fabricated ornamental wooden doors, windows, chests, pulpits, and blinds that were mostly used in mosques, gravesites, and holy shrines such as the Imam Reza shrine in the city of the, Mashhad in Khorasan or Hazrat-e-Masomeh shrine in the city of Qom. Decorations adorning the interiors and exteriors of palaces and mansions such as the Chehel-Sotoon palace, Alighapoo in the city of Isfahan, and Kakh-e-Golestan in Tehran are equally masterful. Networks of roads, bridges, and way-stations as found for example in Pol-e-Shekaste, Pole-Dokhtar, and Pol-e-Ghamishan in Lorestan, Robat e Sharaf in Khorasan, and the unrivaled Shah-Abbasi caravansaries, served as arteries for transportation. Hydro facilities, dams, canals, and qanats were all architectural achievements of the culture and civilization of Islamic Iran. As for artistic and practical handicrafts, with the expansion of the weaving industry and the production of textiles and the weaving of small and large silk and wool carpets in places such as Kashan, Qom, and Isfahan, as well as exquisite ceramic pieces manufactured in Neishaboor, Kashan, and Mashhad, Iranian creativity shone through centuries. Later, gold-hued ceramic pieces and tiles were produced. To these were added gold, silver, copper, and bronze vessels, and pieces, including those festooned with silver. As for literature, Iran saw the creation of manuscripts and illustrated books, including hand-written editions of Shah-nameh, Kelile O Demneh, and Maghamat-e Hariri, and the incorporation of calligraphy, mainly to inscribe Koranic verses, Hadith, and the poems of poets who wrote in Persian, on the face of buildings or different objects such as the tablets found in Masjid-e-Shah or Masjid-e Sheikh-Lotfollah mosques in Isfahan; various albums, including Shah-namehBaysonghori and the Moragha-e-Golshan albums, gave vent to Persian ingenuity and Iran Islamic mysticism. Finally, the creation and development of many metropolitan cities such as Isfahan, Shiraz, Tabriz, and Tehran nurtured a plethora of Iranian communities, prospering as centers of artistic, literary, and scientific creativity.