Isfahan Great Bazaar and its labyrinth's historical sites

The life of Eastern societies has been concentrated around the bazaar since ancient times. The name "bazaar” has its roots in the Old Persian language. This Persian word followed the trade routes and was borrowed by many European and Asian languages. In Iran, the earliest reference to the bazaar dates from the 8th millennium B.C. The legend of Jamshid that appears in the Avesta, the Zoroastrian sacred book, tells of the bazaar already in existence. An archaeological survey in the Sialk Mounds has revealed that the residents of Sialk traded with the countries of the Persian Gulf in about the 5th millennium B.C. and that they could purchase necessities at a permanent marketplace. The records of the Achaemenid period include the costs of goods in the markets and the amounts of taxes levied on the merchants. During the Parthian period, the economy of the country was mainly based on agriculture and trade. Moreover, the Parthians, who actively traded with the countries of both East and West along the Silk Road, even had a monopoly over some specific goods such as spices and fabrics. The map of the Parthian town of Dura-Europos from 165-256 A.D. shows the exact place of the main bazaar of the town. During the Sasanid period, the traders and artisans were already organized into guilds, and each guild had a leader who usually worked as a mediator between the common people and the government officials. Starting from the early Islamic period, the bazaar has not been only the place where trade is concentrated; in fact, it constituted the focal point of most cities on the merchants. During the Parthian period, the economy of the country was mainly based on agriculture and trade. Moreover, the Parthians, who actively traded with the countries of both East and West along the Silk Road, even had a monopoly over some specific goods such as spices and fabrics. The map of the Parthian town of Dura-Europos from 165-256 A.D. shows the exact place of the main bazaar of the town. During the Sasanid period, the traders and artisans were already organized into guilds, and each guild had a leader who usually worked as a mediator between the common people and the government officials. Starting from the early Islamic period, the bazaar has not been only the place where trade is concentrated; in fact, it has constituted the focal point of most city activities. People gathered in the bazaar not only to purchase, but also to communicate, listen to the decrees announced by royal heralds, and to participate in festivities and other ceremonies.

On religious mourning occasions, the bazaar was usually closed. Since the Safavid period, the Esfahan Bazaar has been the place of the most splendid ceremonies, particularly connected with the Moharram mourning rituals. The bazaar has always had an important social power. The cancellation of a tobacco concession in 1890, the Constitutional Revolution of 1906, the nationalization of oil in 1951, and finally the Islamic Revolution of 1979, spurred the closing of the bazaar. The merchants and artisans staged a walkout in objection to the governmental deeds, and all the life in the country came to a stop. In virtually all towns, the bazaar is a covered street, or series of streets and alleyways, lined with small shops grouped by service or product. In small towns, the bazaar might be the equivalent of a narrow, block-long street; in larger cities, the bazaar is a warren of streets that contains warehouses, restaurants, baths, mosques, and Madresehs, in addition to hundreds and hundreds of shops.

|

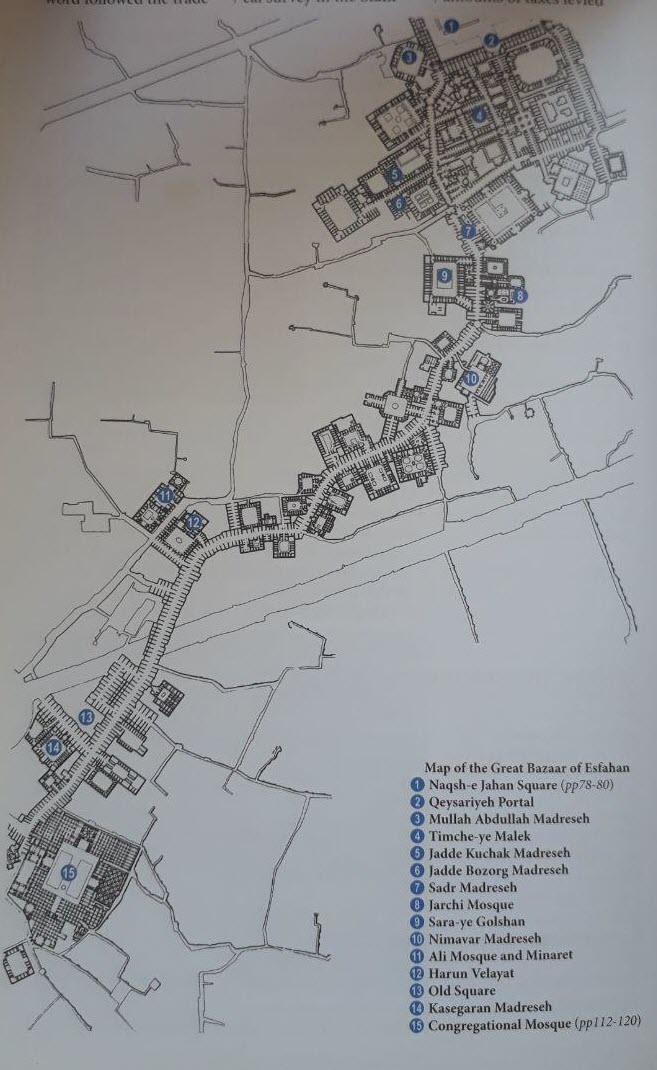

A bazaar usually consists of Raste ye Asli, the main street that, in its simplest form, is a road lined on either side by shops. In large bazaars, Raste ye Faree, auxiliary lanes, branch off the main road. The intersection of two major bazaar lanes is called Chahar sou. Usually, the richest shops surround this point. Meydan, the square, most often precedes the entrance to any bazaar. The Esfahan Bazaar is confined between Naqsh-e Jahan Square at its southern end and Old Square 13 at its northern end. Jelokhan is an area usually enclosed on three sides and fronting the main portal of a bazaar. Hojreh is a small shop specializing in particular goods. If the shop is two stories high, its ground floor is likely to be the shop itself, while the upper floor may serve as an office or a workshop. Caravanserai is usually the most decorated area inside any bazaar. It consists of an open courtyard surrounded on its four sides by rooms for travelers and warehouses for goods.

In caravanserais outside the city proper, a large area was also reserved for stables Timcheh was originally a small caravanserai. Today it is instead a roofed area surrounded by shops, mainly trading in carpets and other valuable goods. Esfahan boasts one of the richest bazaars in Iran. The first record of Esfahan's bazaar comes from the accounts of Naser Khosrow, who visited it in the early 12th century and described it in enthusiastic terms. Although it had thrived throughout the Buyid and Seljuk periods, the bazaar of Esfahan was given new life during the Safavid rule. The grandiose plans of Shah Abbas's redecoration of the capital were first and foremost aimed at securing its economic growth. At this time, the original bazaar, which had been concentrated in the vicinity of the Congregational Mosque, was extended by building a new and larger commercial area to the north of Naqsh-e Jahan Square.

The entrance to the bazaar, fronting on the central square and in perfect keeping with its dimensions, was built in 1619 and is called Qeysariyeh. The name "Qeysariyeh" literally means "Caesarian" and is used to identify the Royal Bazaar. Deeply recessed from the surrounding shops and very high, this majestic gateway is ornamented with tiles and exquisite mural paintings, now perfectly restored. The tiles above the door depict Saggitarius; Oriental writers maintained that Esfahan was under the influence of this sign. The frescos attributed to Reza Abbasi show scenes referring to Shah Abbas's war with the Uzbeks, along with scenes of hunting and feasting. The entrance to the bazaar was once topped by a large clock, which had been made for Shah Abbas by an Englishman named Festy. After Festy's death, the clock stopped, and no one could repair it. Above the clock hung a big bronze bell, looted from a Portuguese nunnery at Hormoz. It was never sounded, and in about the year 1800 was melted down for cannon. At roughly the same period the clock also disappeared. At the time of the Safavids, orchestras in the Drum House on the upper galleries of the Qeysariyeh Portal used to drum and trumpet the sunrise and sunset, and they are also reported to have saluted Shah Abbas's victories in polo games. The Drum House was demolished during the Qajar period.

|

The Esfahan Bazaar has sections from perhaps every period of the city's history. Its most important parts date from the Buyid, Seljuk, Mozaffarid, and Safavid periods. During the Qajar and Pahlavi rules, about two-thirds of the bazaar disappeared. It happened primarily because of the erroneous governmental policy that allowed the import of foreign goods to the extent that it harmed and sometimes destroyed local producers. For example, English textiles, often sold at dumping prices, completely replaced the fabrics of Kashan and ruined Kashan's textile industry to the point that it has never fully recovered. The sale of local tobacco in Esfahan is said to have decreased from | 300,000 pouches in the mid-19th century to 5.000 pouches by the late 19th century, while the rest was provided by foreign merchants. Secondly, during the 20th century, the majority of Iranian cities were replanned and modern, straight streets were laid out. Very often this happened at the cost of ancient lanes and trade streets. Thirdly, modern factories tended to be built on the city outskirts, while modern trade centers were constructed along the new streets. All these factors have diminished the role of the bazaar as the main center of the city's manufacturing and trade. However, although the Esfahan Bazaar has not remained unaffected by these events, it is still a very important center of Esfahan's commerce. It is a labyrinth of arcades, squares, courtyards, depots, and caravanserais. The one-third that is left still occupies an entire district of the city.

Esfahan bazaar merits at least a half-day stroll, not necessarily for buying, but for the oriental atmosphere of haphazard activity. Light streams down into the bazaar's alleys from apertures and windows so high that one could think one was in a Gothic cathedral if not for the insistent bargaining and animated conversations. Those who seek picturesque sights may be slightly disappointed, but here it is daily events rather than objects which are picturesque.

Isfahan's Bazaar, one of the Main Pillars of Power

History clarifies that there have been three main pillars of power consisting of the Bazaar (emporium), Jame Mosque', and Citadel or Administrative Palace. Religion has always played a particular role in the life of the people so in the vicinity of the mosques, some other religious places such as shrines, cemeteries, and public places like bathhouses and schools are set up. "Jame mosques normally adjoining the bazaar, with a huge dome to be seen from a far distance and a four-porched design practically as the center of religious and social gatherings. According to history whenever there was an alliance between the bazaar and the mosque, an enormous thrust formed against the governing body. Consequently, no ruler could ever resist a skirmish with this unity. In other words, the three mentioned poles should be enjoyed, an interlocking relationship to be fully effective.

The segments of the bazaars' cloistered lobbies and corridors connecting the shops have junctures at some points, which carry a high-based dome called; Chahar Sough. The arcades are mostly designed in the proximity of the main bazaar with the main courtyard; accessible for the settlement of handicraft workshops offices, caravanserais, mosques, theological schools, and other public or private places. The main activity, in the bazaar, focused on the endeavors of merchants in caravanserais typified by the main yard, a pleasant pool in the center, piles of parcels, and goods where the wholesalers used to receive their colleagues with a cup of tea.

The caravanserais were often built on the path of caravans in commercial areas and trading centers to store the required goods of the merchants. Until some decades ago, one could find all the components of the trade cycle in them; merchandise, goods, and beasts of burden. After the advent of modern transportation, the old texture of the bazaar gradually undermined the economy, but the old functional spaces historically are of high importance. Although for the renovation of the textures in the bazaars some measures have been taken by the Cultural Heritage Office, modernism has had an immense negative impact on the traditional form of the bazaars, but still one can find an abacus hanging on the wall used in calculating profits.

|

-The Aesthetics of Combined Elements in the Texture of the Bazaar

The texture of the bazaar, today, is similar to a labyrinthine bazaar with a long, high-rise, spacious area having some junctures topped by lofty domes (Chahar Sough). A visitor looks at the columns of oblique or vertical light filtrating through the apertures, made of the reflection of light on dust. After splashing water on its dusty trail, a distinctive smell rises from the mud. The shops are replete with eye-catching and tempting goods with golden and silvery colors, the voice of an ambulant dervish (fakir), and travelers with dazzling eyes create a fascinating setting. Thus, rarely can one find a stern visage there; the place where its ornamental elements are reminiscent of galaxies on the concaves of its vaulted ceilings.

-Qeisarieh The Main Portal of the Royal Bazaar

This portal, as the main entrance to the Royal Bazaar, was built contemporaneously with the portal of "Jam-e-Abbasi Mosque during the time of Shah Abbas I. According to the chronicle of Eskandar Beik Torkaman (17th century), it was built in 1619 A.D., but in another reference called: 'Oesas ol Khaghani the Bazaar was constructed in 1605 A.D., and its portal (Qeisarieh) completed in 1617 A.D.

It was described by "Pietro Della Valle (17th century) as follows: "The main entrance of Qeisarieh Bazaar is across the portal of the Jam-e-Abbasi Mosque in the square with some annexed chambers, where every night drums are beaten there by two persons (Naghareh Chi). On its spandrel, there is an attractive mosaic work depicting the Archer, the astrological sign of Isfahan with some disparities in design. For example, Sagittarius is a constellation with the head and shoulders of a human and the body of a horse; however, here the body is a tiger, its tail is a dragon that opens its mouth towards the human part."

Qeisarieh was also explained by Chardin (17th century) in this way: Besides its mosaic decoration, it has some mural paintings. One of them hints at a battlefield showing the dominance of Shah Abbas I, over the Uzbeks. On both sides of this panel, one observes the visages of some Europeans sitting around a table, drinking and becoming drunk. These paintings were probably added during the reign of Shah Abbas II, contemporary with Chehel Sotoon or Ali Qapu palaces.”

Qeisarieh Bazaar functions as a transition element between the central zones of the old texture (11th century) and the new one (17th century). It was counted as one of the power centers, therefore, the Safavid king decided to build it for the development of trading and acceleration of economic growth in the close proximity of the royal complex.

|

After the completion of Qeisarieh Bazaar, in 1622 A.D., Shah Abbas I ordered to install a clock and a belfry over it, which were among those of the booties of his triumph over the Portuguese in Hormoz, as symbols for victory over a famous colonialist nation. At the same time, some booty such as a large number of cannons is arranged on both sides of Ali Qapu Palace. The Bazaar covers a considerable large area and at each of its corners, into the shops, there are workshops, public-drinking places, caravans saues, bathhouses, oil pressings houses, and theological schools. The places, caravans dimension of the Bazaar de pension of the Bazaar designed in harmony with the circulation of the cars pressings houses, and vans of camels and carriages Its plan was copied later as a typical pattern for building bazaars in other cities textures. On the crossroads of the Bazaar, some high-rise domes with more elegant ornamental elements called, "Chahar Sough' (four bazaars) cap the area. Amongst so many caravansaries, one is known as Shah Caravansari counted as the largest, built-in two stories Olearious, while visiting the Bazaar in 1637 A.D. explained it as There are so many supplies of precious textiles and objects of high value from all over the empire that scarcely can one find such valuable things in other parts of the world.

-Naghareh Khaneh, the Historical Drummers Chamber in Esfahan

Since ancient times, beating drums at regular intervals was common in some of the territories of the orient. Different types of drums, accompanied by trumpets and horns, were taken to the battlefields to synchronize the warriors and intensify their patriotic feelings, or to keep them alert before any struggle.

During peace, time, they were used by the Mithraists (the sun worshippers) while holding their ceremonies. For example, the Mithraists assumed that during dawn (reveille) and dusk (tattoo) they should receive and bid farewell to the sun as a sign of respect and welcome each region for the prevention of a probable solar eclipse which was considered a catastrophe. Today we know the sun's radiations during the solar eclipse cause destructive effects on the eyes. The drums were also beaten on some other occasions to inform the people about holding festivals, kings' ascending onto the throne, the movement of an army, or to alarm people in case of an emergency. The performance of beating drums has been reflected in Persian poetry. A line of poetry, composed by Nezami Ganjavi indicates their importance of them:

What happed to the drummer at dawn,

Methinks the beat forgotten in the town.

Hafez also describes the beating of the drum in his poetry as follows:

No drum, no cymbal was beaten tonight, substitute, Seems as if, no lighting ends the darkness of solitude. The drums of reveille and tattoo were beaten in Esfahan until half a century ago in the particular chambers of Qeisarieh, the main portal of the Royal Bazaar in the northern part of Naghsh-e-Jahan' Square.

|

Isfahan Bazaar map and its historical sites

|

Mullah Abdullah Madreseh

|

Located at the very beginning of the Great Bazaar, this seminary is one of the earliest in Esfahan. It was built in the time of Shah Abbas I for Mowlana Abdullah Shushtari, one of the most prominent theologians of that time. The layout of the Madresch is quite typical for Iranian religious structures. It includes a courtyard that is enclosed by two-story arcades of students' lodges. ings. The facades of the arcades are decorated with tilework. The inscription on the portal indicates the repairs were completed at the directive of Fathali Shah Qajar in 1803. * Women visitors and taking pictures are not allowed in any of the seminaries.

-Malek Timcheh

This section of the bazaar was built in 1904 during the rule of Mozaffar al-Din Shah Qajar. The building consists of three consecutive vaulted areas, two stories high and each surmounted by a skylight, through which light streams inside this beautiful area. In the middle of the hall lies a large pool. Brickwork is of exceptional quality, and it is highlighted sparingly by brightly colored tiles. Through a short passageway, facing the entrance area, the Timcheh is linked to the rectangular courtyard of a small caravanserai. The caravanserai consists of multiple chambers, with the upper floor supported by a columned arcade in front of the ground floor. An oval pool, matching the elongated form of the yard, occupies its center.

-Jadde Kuchak 6 and Jadde Bozorg Madreseh

|

These two colleges from the time of Shah Abbas II were built in 1647-48. They are based on a similar plan but differ in the terms of the occupied areas. What is called Bozorg ("big") was originally called Kuchak ("small"), and commemorated one of Shah Abbas's ancestors. However, now the names of the seminaries correspond to their sizes. Both colleges feature portal inscriptions in Tholth done by Mohammad Reza Imami.

-Sadr Madreseh

One of the largest and most impressive Qajar buildings in Esfahan, it was founded by Hajj Mohammad Hossein Sadr Esfahani, the minister of Fathali Shah, and is the most conspicuous of his creations. During the long period of its work, the seminary trained many notable theologians in various branches of religion and law. The library building is a 20th-century commission. The seminary features an impressive number of fine calligraphy, of which inscriptions in Nastaliq are particularly magnificent,

- Jarchi Mosque

|

The Jarchi Mosque belongs to the reign of Shah Abbas I and was constructed by Jarchi Bashi (Chief Royal Herald) in 1610. In the time of Shah Abbas, it was common for the rich to spend money on religious buildings. Curiously, after Shah Abbas I, no other Safavid shah built a mosque, and all the later mosques were constructed by wealthy people. The mosque consists of a single prayer hall. Its decorations include fine paintings and tile mosaics.

- Golshan Caravanserai

This large caravanserai consists of single-stories chambers, arranged around a courtyard with several pools and flowerbeds. An important feature of the | building's design is the location of the entrances at the corners of the courtyard, with a small pool in front of each entrance. The arches of the chambers surrounding the yard exhibit a harmonious rhythm despite their different dimensions. A network of corridors links the main structure to numerous auxiliary areas, among them open-air parking (formerly a lading area), lanes of commercial shops, and a mosque. On the western side, there is a small handsome Timcheh, which is unrelated to the caravanserai and accessed directly from within the bazaar.

- Nimavar Madreseh

Another relic from the Safavid period, it was built during the rule of Shah Soleiman in 1705. The decorations include lavish tile and stucco ornamentations, of which a good many have survived, and several Nastaliq inscriptions. Mosaic panels of painted plaster also constitute a unique element of the decorative treatment of the structure. The Madrasah is one of the most reputable theological colleges in Esfahan.

- Ali Mosque and Minaret

|

The Ali Mosque is easily found because of its minaret - the most conspicuous of Esfahan's landmarks. The building was originally a Seljuk construction. It was built by Mahmud Seljuk, who governed in Esfahan for fourteen years and was named after Sultan Sanjar, his uncle and father-in-law. However, by Safavids' time, the mosque had already been ruined. The portal inscription in golden Tholth indicates that the mosque was rebuilt in 1522 by Shah Ismail. At that time, the Safavid monarch renamed the building after the first Shiite Imam - Ali.

The architectural techniques of the mosque and its superb ornamentation place it among Esfahan's most important religious structures. The mosque is entered through a western Eivan, which opens onto an orderly court. The brick dome of the sanctuary, located behind the imposing southern Eivan, is decorated on the inside with pretty paintings and graceful Moqarnas. An interesting detail of the building's architectural layout is that its winter prayer hall is located lower than the sanctuary and is reached by a descending flight of stairs.

Dominating the corner of the mosque, the minaret is perhaps the earliest in Esfahan, built around the close of the 11th century. It is also the highest, rising to 48 m. The shaft bears very interesting geometric patterns, executed in brick, as well as four Kufic inscriptions. Of these, one is of brick, and the rest are of turquoise tiles.

- Harun Velayat

Opinions differ as to the origin of the person buried in this mausoleum: some report that he was a son of the ninth Shiite Imam, others call him a son of the tenth Imam, while still others consider him to be a grandson of the sixth Imam. Whoever he may be, the mausoleum created on his grave is believed to be the most important vestige of the early Safavid period in Esfahan. The shrine was built under Shah Ismail I in 1512 by Ostad Hossein, possibly the father of the architect of the Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque. A spacious courtyard, lined with pilgrims' lodgings, was added in the 19th century as part of the repairs made during the reign of Fathali Shah Qajar. The shrine is noted for its tiled dome, which is considered to be one of the finest in Esfahan. Also notable are the superb arabesque designs of mosaic tilework, Kufic inscriptions at the base of the dome and on the portal, and some intriguing murals at the entrance to the shrine. The sanctuary chamber of Harun Velayat has been converted into a Hosseiniyeh and is only open when the Moharram passion plays are performed there, but the shrine itself is open at all times.

- Kasegaran Madreseh

This seminary was created at the time of Shah Soleiman Safavid. The Thoth inscription gives its date as 1693 and the name of Amir Mohammad Mahdi Hakim al-Molk Ardestani as the building's founder. The seminary is housed in a handsome building that is richly decorated with tilework! and calligraphy. Graceful Mogarnas of the niches and vaults also add to the beauty of the Madrasah.