Copyright 2020 - 2021 irantour.tours all right reserved

Designed by Behsazanhost

Natanz

Natanz

Although there is no mention of Natanz until the 13th century, it can possibly be one of the earliest human settlements on the Iranian plateau. Its favorable geographical position in a picturesque valley backed by the imposing bulk of the Karkas Mountain, on the one hand, and the proximity to the important trade and caravan routes, on the other hand, account for the town's crucial importance to the country's economy throughout various historical periods, especially during the Seljuk and Safavid rules. The town was an important center of the Il-Khanid Empire, and the complex of its outstanding religious buildings dates from this period. Of pre-Islamic structures, a ruined Sasanid fire temple has survived in the town. Natanz had been ruled by Esfahan governors until the Safavid period when it was granted special privileges and was controlled directly from the capital, which was first in Qazvin and then in Esfahan.

|

Shah Abbas I, who spent quite a lot of time hunting around Natanz, virtually turned it into his summer capital. Natanz enjoyed its independent position until about fifty years ago when it was again subordinated to Esfahan. Although the area has several minor rivers, its water is mostly supplied through the extensive qanat system. It helps to maintain agriculture, the principal products of which are wheat, oats, haricot, various vegetables, and fruit, mostly pears, which are believed to be the best in Iran. The area surrounding Natanz has numerous gazelles, ibex, and quail, which make it an important hunting center the area (at present, however, hunting is strictly regulated here). Natanz's attractions can be seen during a day trip. Additional time is needed for a visit to the 15th-century fortress of Qal'e-ye Voshaq and to the Falcon's Dome.

|

Congregational Mosque

A conglomeration of buildings, which are the most important Islamic relics of Natanz, consists of the Congregational Mosque, the mausoleum of Sheikh Abdolsamad Esfahani, a portal of a ruined Khaneqah, and a minaret. Except for a domed prayer hall of the mosque, dating from the Buyid era, the other structures were built in 1304-1325 and belong to the Il-Khanid period. The complex is surrounded on three sides by narrow alleys. The alley on the south side forms a small square, where the entrance to the mosque and the facade of the Khaneqah are located. Here grows a remarkable plane tree 0, whose immense size is surely indicative of its long history.

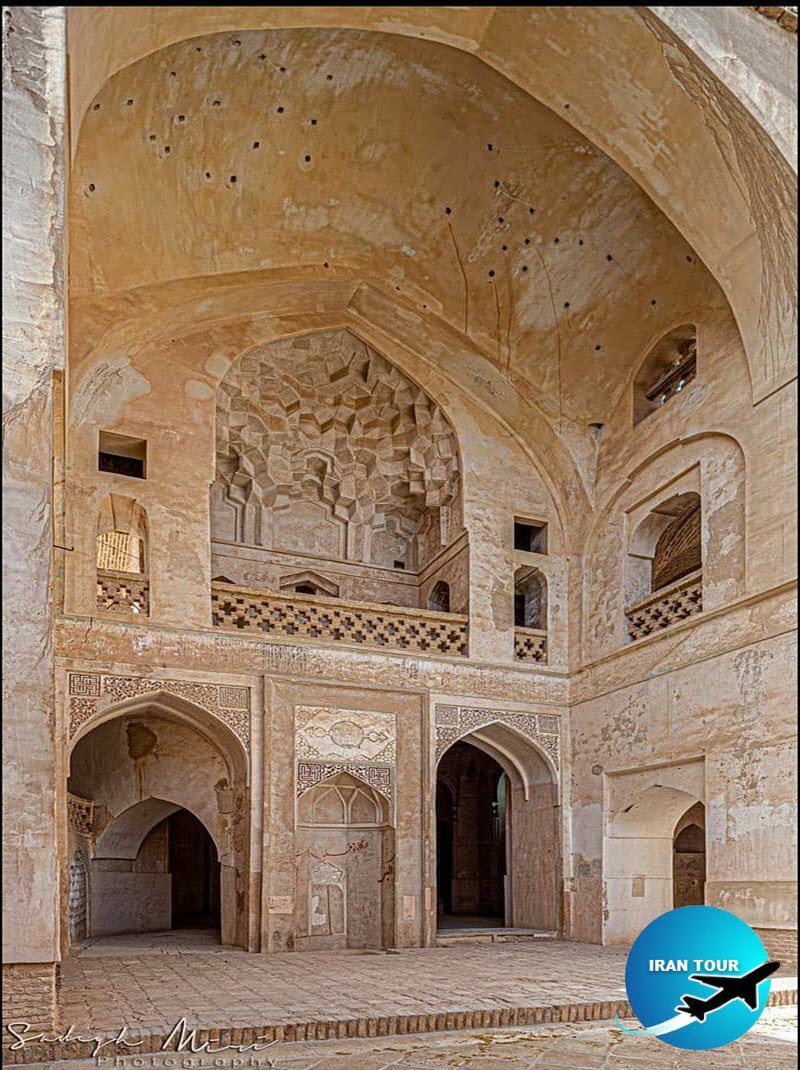

The mosque was surprised with its fanciful layout and lack of decorations. It has three entrances, the one on the south 3 (today the only open one) leading to the mosque by a flight of twelve steps. The mosque was built in 1304, and this date, along with the names of its founders, is written in blue-glazed letters on a yellow background of the south eivan as was customary in Il-Khanid architecture. The mosque was built on a four-eivan plan, and the Buyid prayer hall was incorporated into the structure in a very elaborate way. In the middle of the courtyard, eight steps lead to a qanat, from which visitors can still obtain drinking water.

|

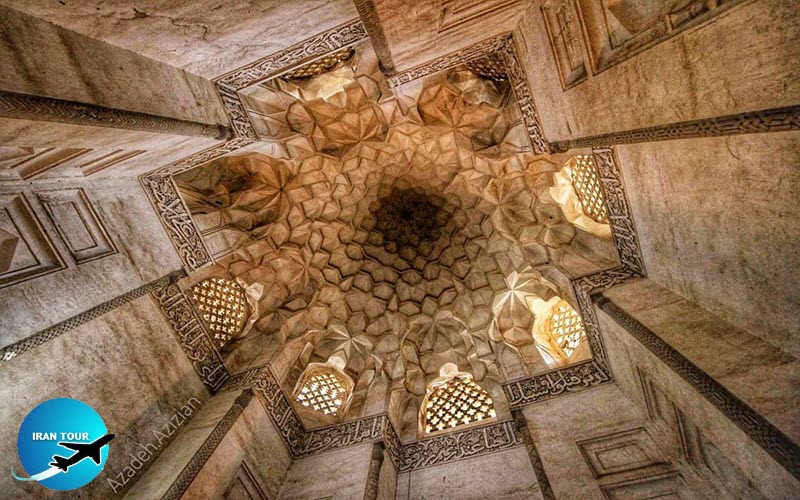

The south eivan is not at all as sumptuous as is common in most Iranian mosques. It features a fine plaster-decorated mihrab, flanked on either side by two vestibules, only one of which (right) leads to the domed sanctuary 6. This prayer hall was originally built as an octagonal kiosk in the 10th century. In the 14th century, when the mosque was essentially remodeled, it was converted into the sanctuary of a four-eivan mosque. It is, however, displaced in relation to the axis of the south eivan. The shallow brick dome is dated 999, making it the oldest dome with a historical inscription in the region.

The north eivan is most remarkable for its lofty arch and interior plaster decorations. The inscription in Tholth script on a blue plaster background includes verses from the Koran. On the two sides of the north eivan, there are two roofed vestibules. Through the western vestibule, the visitor enters a small anteroom and then a larger one connected to the court on the one side and the northern entrance corridor on the other side. Following it, the visitor can reach an ancient inlaid door, which, according to its inscription, was made in 1563 and installed on its current site in 1603.

|

The east eivan is the largest of all but lacks any kind of decoration. In its northern passage, there is a fine fireplace with some plaster adornments. In the southeast corner of the court, a two-story prayer hall 10 is located. Its ceiling is supported by six bulky columns and two half-columns. The prayer hall has two windows facing the south eivan, two windows facing the east eivan, and a window facing the yard. The ceiling and walls of this prayer hall feature plain plaster moldings.

The west eivan is the smallest and is without decoration. The difference in the porticos relates to the design of the structure. The rule of symmetry was strictly followed during the building of the mosque. A new prayer hall 2 was built in 1996 on the site of the ruined khaneqah.

|

| Sheikh Abdolsamad Esfahani Dome |

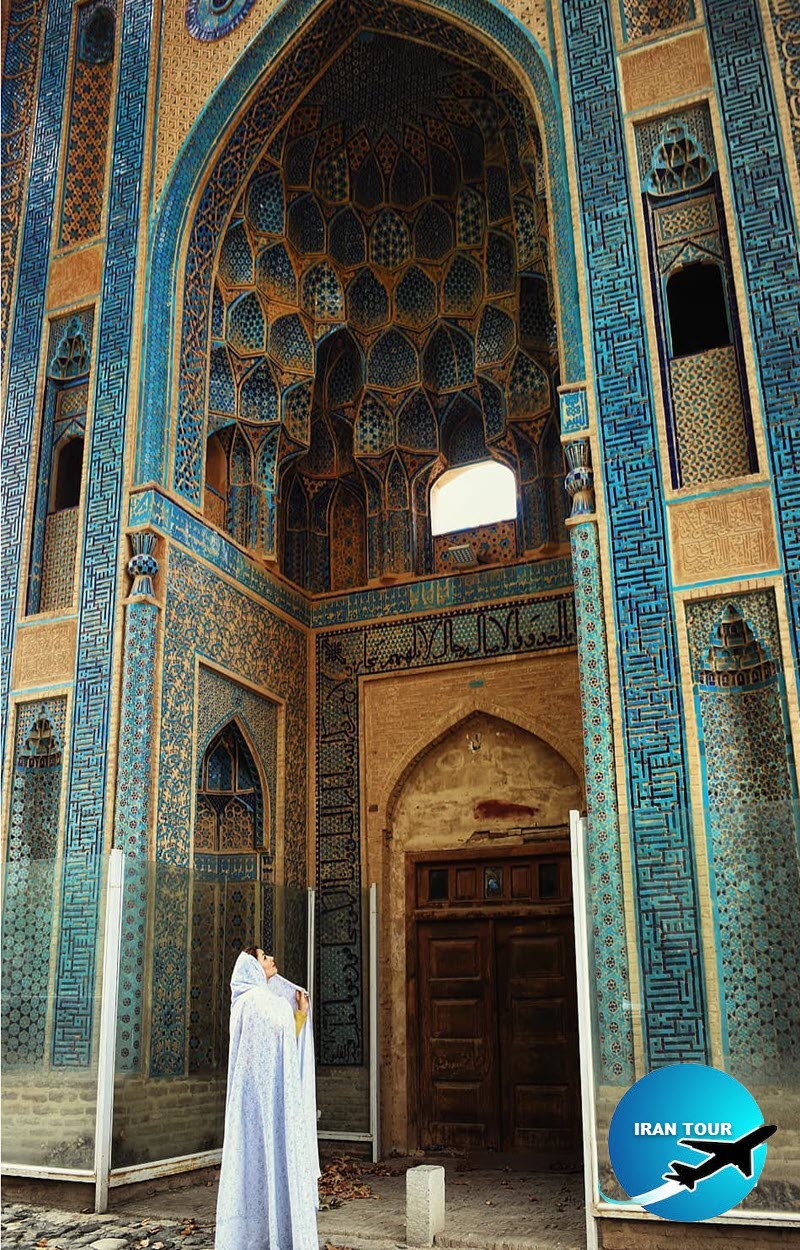

To the west of the mosque's southern corridor is the Mausoleum of Sheikh Abdolsamad Esfahani, the 14thcentury Sufi. It comprises a rectangular room with a pyramidal dome, embellished with turquoise ceramics on the outside. The scarce remains of tilework inside the mausoleum, practically all of which have been plundered, give a hint of their original beauty. Today the mausoleum's only decoration consists of superb Moqarnas of the dome's interior, a Tholth inscription running along the dome's perimeter, and a wooden sarcophagus.

Only a portal has survived of the Sheikh's Khaneqah, but this is inarguably the most important element of the entire complex. This impressive facade was built in 1313. Its tilework resembles in quality and designs the contemporary work at Sultaniyeh. It is likely that, upon the completion of Oljeitu's tomb, craftsmen were dispatched throughout the empire to ornament religious and public structures. The tiles are laid in beautiful combination, with bricks arranged in geometric designs. Several fine inscriptions in Kufic, Reyhan, and Tholth complete the portal's decoration. The Khaneqah itself existed until the end of the Safavid period, but was ruined after the Afghan invasion and never restored. Its superb mihrab (dated 1307) was looted at the end of the 19th century. Today London museum-goers can see it in the Victoria and Albert Museum. The tall brick minaret features beautiful tilework and an inscription dated 1324. It is 38 m high. Located in the complex's vicinity are a large Hosseiniyeh and a shop that sells distinctive local pottery.

|

Fire Temple

Nothing remains of this Sasanid Chahar-Taq, built of stone and gypsum, except the pillar bases and one of the arches. Nonetheless, this is the most ancient structure in the town and may be interesting to antique lovers. To get to the temple, take the footpath along the side of the Khaneqah to the north and follow it past a cluster of dwellings.

Kucheh Mir Mosque

This mosque could have been easily omitted from the list of Natanz's attractions if not for its magnificent mihrab of chiseled stucco with floral design. Done in Seljuk style, the mihrab is actually all that has remained of the original building. The mosque dates from the 12th century, but it was later so excessively rebuilt that nothing has survived from the original two-story structure except the mihrab.

|

Falcon's Dome

Perching on the crest of a steep mountain to the southwest of Natanz, the Falcon's Dome can be called the most unusual Iranian building. Climbing the precipitous path (2.5 km) up to it is quite a challenge, and though the western slope is gentler, the site is recommended only for the most sporty and adventurous tourists. The building is based on an octagonal platform and a lofty arch pierces each of its sides. The structure is entered through the northwestern corner, where a flight of eleven steps remains The column bases and the platform has been awkwardly scraped, and looters excavated the floor in search of treasures. This led to the roof's collapse and has threatened the structure itself.

What is most remarkable about this building is its overwhelming story. It says that Shah Abbas I Safavid, hunting in its whereabouts, became thirsty. When he, at last, found a water spring, his falcon suddenly attacked him and did not allow him to drink. Angry at the bird, the shah killed it. When he bent down to drink, he saw a snake (or, in some versions, even a dragon) that spit poison into the spring. In great remorse, the shah decided to build a mausoleum for his favorite bird. Although building a mausoleum for a bird sounds extravagant even for Iranian history, in which everything seems to be possible, and the story has undoubtedly been embellished with fantastic details, the fact remains that the building was indeed built over the grave of a falcon. How the huge stones were brought up to the top of the cliff remains a riddle that is unlikely to be ever solved. At the foot of the cliff, is a popular recreation site called Qadamgah-e Ali, indicating that Imam Ali stamped his foot at this place. With the loquacious spring and bunches of plane trees, it is a good place for picnicking

Arisman

A vast area of some 3 sq. km in the northern foothills of the Karkas Mountain is an important archaeological site. Research into ancient smelting activities is being conducted here. The primary investigation has revealed that copper and gold items were produced here and that Arisman could have been one of the oldest metallurgical sites in Iran (and perhaps in the world). The scope of the project is immense as the site also seems to be the world's largest ancient industrial I city so far unearthed.

- Details

- Category: Where to go in IRAN